JENNY LEWIS: MOTHERHOOD AND MISCONCEPTIONS OF A MALE GAZE

When my girlfriend first showed me pictures from Jenny Lewis’ One Day Young project my initial reaction was one of rejection.

In a split second I rejected the portraits of mothers holding their newborn infants, within twenty-four hours after giving birth, as rose-tinted sentimentality tugging on the heartstrings of hormonal women. I rejected it as simplistic and insipid.

Over the following couple of days Lewis’ project crept in to my consciousness, however, and I began to question my reaction. As a man in his mid-thirties I am surrounded by friends, family, peers and strangers constantly talking about babies – trying for another, first scans, miscarriage, childcare, first day of school, birthday cakes, My Little Pony, One Born Every Minute, screaming next door, changing nappies, Peppa The Pig all the fucking time. You see, being in no hurry to start a family one tends to find oneself on a separate road to many others. Despite the same old clichés about wild-oat-sowing men, most do look forward to fatherhood just as women do with motherhood. But in my case as in many others, it can be quite draining to be made feel like I’m stubbornly walking a race the rest are running freely. Just because men do not have the same body-clock imperative as women, does not mean that they are impervious to similar pressures.

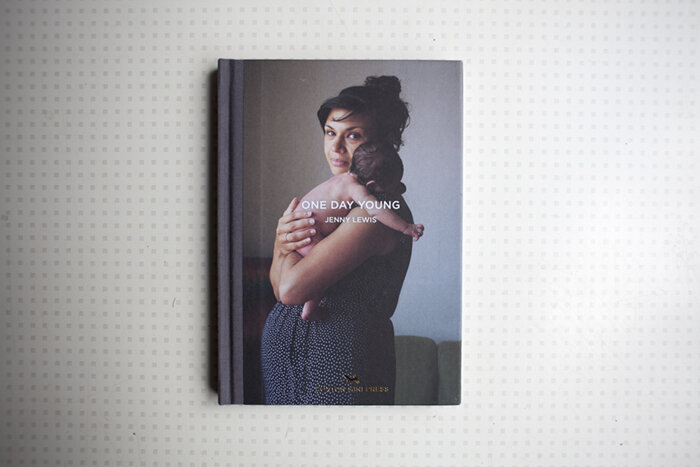

So this initial rejection of One Day Young was based on my own personal circumstances as a male at a certain time and place in my life; which is unfortunate, as it said more about my own anxieties and insecurities than it did about the beautiful portraits Lewis has spent five years making in her local borough of Hackney in East London. Another reason for the reaction could be a more deep-seated problem of societal misogyny where the idea of celebrating women in such a way could be viewed as an undermining of the male supremacy. These happily exhausted women, standing proudly with their reddened infants barely able to open their eyes, don’t appear weak or unsure, naïve or insecure. As visible in the portrait of Liana and Archer, there is strength and unfettered accomplishment. Obviously the mothers are full of pride and hope, and as the inscriptions within the pages of the book state quite clearly, they are contemplative and insightful – they may be full of endorphins and hormones but they are nobody’s fools and more focused than any one person could be. In essence, the portraits assert a gender-specific role that has often been usurped by patriarchal politics in a way to subjugate the female creator rather than celebrate her in her own right. And this can scare some of us males without us even realizing it.

I talked to Lewis about her project during the Format International Photography Festival Portfolio Reviews in March 2015, and following our session I raised the subject with male colleagues in an effort to gauge their response. One individual mentioned the fact that the fathers were not present or suggested in the images, effectively relegating each father to a faceless sperm donor. He seemed to be offended by the one-sidedness of the project. Yet this completely misses the point Lewis is making with One Day Young, that it is the mother who carries the child for the best part of the year, that she is the one who has her life completely turned upside down both physically and mentally (and professionally), and then it is she who must endure the pain and anguish of giving birth. It is the mother who literally does all the hard work, so why shouldn’t we as an enlightened society acknowledge, support and respect the achievement in more ways than a Hallmark card or a bunch of flowers. Why can we not pay homage without it being just about them? Ultimately this does not relegate the role of the father in the grand scheme of things, but it does put some perspective on the argument.

The portraits in One Day Young are a simply constructed motif of mother holding baby. Taken in each mother’s home and naturally lit there is a visible comfort with each face telling a slightly different version of the same story: some births are more difficult than others, while some come with a shadow of tragedy before or indeed after the first twenty-four hours. It is worth remembering this small and handsomely produced photobook depicts the beginnings of a journey no one person before or behind the camera can envisage. Despite this very short moment of concise capturing there is an underlying fragility and tenderness that speaks of life’s triumph and uncertainty, resolve and vulnerability.

Owing to the huge amount of time and variety of subjects Lewis has photographed there is a rewarding diversity throughout the project. The photographer leafleted her neighbourhood looking for women to take part regardless of age or background and it proves to be a valuable effort in saving the project from becoming too repetitive. It can be a very difficult thing to take on a subject like this without falling into one aesthetic trap or another, or without hindering the conceptual integrity by zealous sentiment. As an artist it is a necessity to choose a subject important to his or her own heart so as to uncover an authentic insight. As a photographer however, it is equally necessary to find an objective view so as to create a meaningful image that captures the subject in a way others can empathize with or be fascinated by. In the case of One Day Young, I believe Lewis has achieved this difficult task and the photobook, published by her local East London Hoxton Mini Press is a testament to that.It will be unsurprising that One Day Young will speak more loudly to women, yet one would hope that the audience (males in particular) understands that while the subject is exclusively about motherhood that is not to say it is about exclusion. Obvious as it may seem, simple as it may be, it is a rewarding aspect to photography that a project such as this can challenge in the most unexpected ways.

.

All images ©Jenny Lewis

You can purchase a copy of One Day Young directly from Hoxton Mini Press